When raising grass-fed beef there are many things to be aware of ahead of time. In this post (and podcasts) I’m sharing my decades of experience.

Raising grass-fed beef on your pasture land is the best way to know that the meat you are eating is truly organic, non-GMO, and hormone-free.

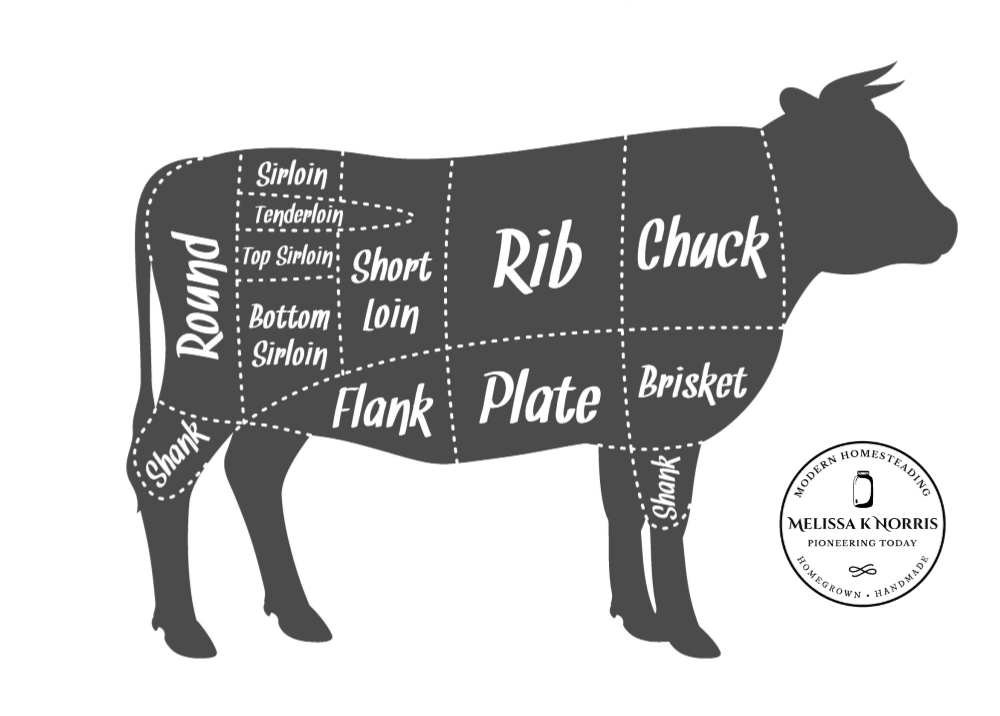

Once you’ve raised up your cattle, then you will be ready to learn everything you need to know before butcher day and the best cuts of meat from a cow.

This post contains two podcasts. The first is episode #426 and is part of my Homesteading 101: Back to the Basics series. The second episode is #23, Raising Your Own Grass-Fed Beef.

Both episodes are my Pioneering Today Podcast, where we don’t just inspire you but give you the clear steps to create the homegrown garden, pantry, kitchen and life you want for your family and homestead.

Growing Up On a Cattle Farm

I grew up on a small cattle ranch nestled against the foothills of the North Cascade Mountains. My father raised beef for years, and it’s one of my favorite memories. White-faced Herefords dotted the green pasture like daisies.

The sound of my father’s old red Ford pickup truck rolling across the dirt track of the long-abandoned railroad track called the herd better than any cattle dog. Besides the few times we ate at restaurants, I rarely experienced the taste of store-bought beef.

When my husband and I married and bought our own butchered beef, I would have benefitted from knowing how to plan for a year’s worth of meat.

We miscalculated the amount we would need, ran out of beef, and had to purchase it at the store until the next butchering time rolled around.

I had never cooked store-bought meat and had no idea how different it was. While the smell and taste were utterly different, I was shocked by the amount of liquid I had to drain off, even though I had purchased the leanest meat.

Benefits of Raising Grass-Fed Beef

There are many great reasons for raising grass-fed beef. Most of the reasons will fall under knowing what’s in your meat. We have now started adventuring into raising Scottish Highland cattle in addition to our regular herd, and the benefits are the same:

- Creating Resiliency – Raising your meat without dependency on the grocery store is always a goal.

- Land Management – If you own acreage and have sizable pasture land, beef cattle will help with brush management, rotational grazing can improve soil, and these methods can rehabilitate pasture.

- Natural and Organic – If you are the owner, you control the animal’s food and medicines, so there is no risk of growth hormones or antibiotics if that is an essential factor in your family’s life. You won’t have to worry about reading meat labels any more.

Grass-Fed or Grain-Fed

When raising grass-fed beef, there are two common ways to fatten cattle for maximum beef production. Grass-fed cattle are strictly given a grass diet through grazing and supplementing with hay in the winter.

Some farmers raise cattle on pasture grasses and supplement their feed with grain. Adding grain quickly adds weight, garnering a heavier weight at butcher time due to more fat.

However, the most common form of grain that farmers use is corn. The detriment of feeding corn is the likelihood that it’s genetically modified (GMO). If you feed cattle GMO corn, those GMOs will also be in their meat.

How Much Property Will I Need?

The recommended number of acres per head of cattle is one in my growing climate (this varies greatly by your rain fall and average daily temps for growing grass). You need to research your area for specific acreage per head of cattle.

However, I would say a safer bet is to have two acres. The minimum is just that, the minimum and doesn’t account for years with severe weather. Two acres in my climate is sufficient for summertime eating and takes into account poor weather years (such as drought). Not to mention, cattle are herd animals, and it’s always best to raise two head of cattle at a time (more on this below).

If you live in a cold climate where the pastures freeze, stop growing or are covered in snow during the winter, you will still likely have to purchase hay for several months’ feed.

Soil health lies at the heart of regenerative agriculture practices. Practicing rotational grazing by moving cattle from one paddock of field to the next will also help improve the soil, resulting in better quality feed for your animals. Be sure to listen to my podcast with Joel Salatin on rotational grazing for a small homestead and my podcast with Deanne Converse on growing your own livestock feed.

If you don’t own enough pasture land to raise cattle, you can always look into leasing property from a neighboring farmer. The general responsibilities of the cattle owner usually include lease payment, maintenance of fencing, and primary care of the cattle.

Another thing to consider when raising cattle is a herding dog. You can learn more about farm dog breeds in my podcast interview with Jordyn Kelly.

How Many Head of Cattle Should I Own?

Cattle are herd animals and feel safest in a herd. It’s best to raise more than one cow/steer. They will be lonely, skittish, and jumpy if single. You may also find a solo cow/steer pushing through your fences in search of its herd.

Regarding how many cattle to raise for one family for beef needs, this depends on your family size and how much beef you consume. The average American family of four will need about half a cow per year. Of course, there are variables, but this is a general average.

Keep in mind that a typical cow/steer takes two years to reach butchering weight, so you’ll need to plan accordingly. Cattle aren’t like pigs, where they’re born and butchered in the same year.

Best Cattle Breeds

When deciding which breed to bring to your homestead, there are a few things to consider. Breed will certainly determine the final size of your cow/steer. However, in my experience (and my opinion), when it comes to flavor, that’s more determined by how that animal is raised and fed along with how it was butchered and processed (including how long it was aged).

Sure, certain breeds can determine the marbling in the meat, which some would say affects the flavor. But in general, for small homesteads, the way it’s raised and fed will be the larger determining factors.

One thing you will want to consider is how well a specific breed does in your climate.

Our Scottish Highland cattle make sense for us in our Pacific Northwest location. However, if you live in the southern part of the United States (or other warmer climates), it wouldn’t make sense because these cows don’t do well in excessive heat.

We also like the Scottish Highland cows because they’re browsers (a little more like goats) and will eat some of the leaves from brambles and low tree branches. However, in the heat of the summer, we have to make sure they’re only on pasture with trees for shade.

A big draw for us was also having our Norris Farmstead vacation rental. We knew if people were looking for places to stay in our area, that the Scottish Highland cows could be a draw which might make someone stay at our rental over another.

Another consideration when choosing a breed is how many years it takes to get them to butcher weight. Scottish Highland cows take upwards of three years. Though they consume less, it’s still a time commitment that must be considered.

Fencing Recommendations

Good fencing needs to be a top priority. The cattle owner is usually liable if they push through a fence and get hit by a car (with the exception of open-range laws which we don’t have in our area).

Cattle are strong and stubborn, and you know the age-old saying, “The grass is greener on the other side of the fence.” If a cow/steer can get its head through a fence, it will usually persistently push until it breaks through.

Some farmers use electric fencing, but we have found that tightly stretched barbed wire and regular maintenance work just as well. Placing metal stays at the halfway point between fence posts helps keep the wire tight.

Shelter Requirements

A barn is not necessary to shelter cattle, but you will need to provide shelter from the elements. Part of our pasture is forested, providing protection from rain and snow and shade in the summer.

Keeping animals cool in the summer heat is just as crucial as providing shelter in the winter cold.

Food and Water

Feed Requirements

Understanding the nutritional requirements of cattle is essential when raising grass-fed beef. As mentioned above, cattle are grazers. If your pasture land produces good-quality grasses during the growing season, the cattle will have sufficient nourishment in the summer months.

Cattle require 2.5% of their body weight in dry feed forage per day. So, for example, if you have a 1,000-pound cow, that equates to 25 pounds of dry-weight forage per day.

- Hay – If you’re feeding dry hay, this is an easy calculation as you’ll simply need 25 pounds of hay per day, per cow.

- Grass Hay – Grass hay contains about 8% moisture content. So, your 1,000-pound cow will need approximately 27 pounds per day.

- Haylage – We feed our cattle haylage, which contains about 40% moisture content. So we’re feeding each cow approximately 35 pounds of haylage per day.

You should also estimate that a few pounds of the hay will get wasted, even when using a feeder. So, it’s wise to add in about 2-3 pounds per day per cow.

Make sure that you have a reputable source ahead of time and know how much that provider can give you each year. Remember that farmers who grow hay have varying amounts depending on the growing year, so make sure you’re on their list and they know how much hay you’ll be purchasing each year.

Pro Tip: It’s always better to have a bit extra each year than to run short and not have enough feed to feed your animals.

Easy Keeper or Hard Keeper

If you’ve ever heard the phrase, “That cow is a hard keeper,” that means that cows are very difficult to keep at a healthy weight. An “easy keeper” is a cow that maintains weight very easily.

It’s important to pay attention to the traits of your animals, especially when breeding your own livestock, to maintain the good-quality traits/genetics in your herd.

Water Requirements

Fresh water is a given and just as necessary in the winter as in the summer. Your work is complete if you have a freshwater source, such as a pond or creek, that the cattle can access. However, not all properties have this.

We’ve used stock tanks and bathtubs as water troughs. Whatever you have that holds water will be perfect. To convert a bathtub into a water tank, simply plug the drain hole and fill it with water from your well; your cattle won’t know they don’t have a fancy stock tank.

Installing automatic waterers will ensure the tank (or bathtub) stays filled. The design of these waterers works to fill the tank when the water lowers to a certain level. Tank heaters are also great for wintertime to keep the water from freezing.

When Is It Time to Butcher?

Butchering time depends on the size of your cow/steer. For example, if you purchase a yearling in the spring, it should be ready to butcher in the fall. You always want to butcher when the cow/steer is gaining weight. More weight equals more beef.

Purchasing a yearling (between 12 and 24 months of age) is more expensive than a calf, as you pay more for a larger animal. However, you won’t need to feed the cow/steer throughout the winter, eliminating the cost of hay.

Most people prefer butchering their steers. Steers are neutered bulls and are larger, giving more meat. We usually butcher when the steer is two years old and has reached a mature weight suitable to our needs. (Here are tips for butchering large animals at home.)

The best cuts of meat to get should be determined by what you know your family enjoys. Don’t be afraid to try the organ meats. You can even use the beef liver to make homemade supplements, or some people get this ground into the beef (most people can’t even tell it’s there).

Breeding Cattle

To keep your herd size growing proportionately to what you need, you must breed the heifers. Breeding is also essential for milk production if you choose a dual-purpose breed for meat and dairy.

While we have been focusing primarily on beef cattle, you can also learn everything you need to know about dairy cows so that you can preserve dairy products, make fermented dairy products, and this easy creamy yogurt.

Cows have a nine-month gestation period, and springtime calving is preferred.

- Natural – Track your cow’s heat cycle and put it with your bull at the right time. If you don’t own a bull, make arrangements with a local farmer to use his bull. Generally speaking, this method is usually more successful.

- Artificial Insemination – This method uses frozen straws of semen to impregnate a cow. This can be a more expensive route and isn’t guaranteed to take.

Keep records and avoid inbreeding by either rotating bulls yearly or either sell or butcher any two-year-old heifers to avoid breeding a daughter back to the father.

Verse of the Week: 2 Corinthians 1:4

Other Posts You May Enjoy

- Planning Our Livestock to Raise a Year’s Worth of Food

- Stocking Up on Animal Feed (+ How Much to Feed Animals)

- When Butchering a Cow the Best Cuts of Meat to Get

- Raising Grass-Fed Beef – What to Know on Butchering Day

- Beef Liver: How to Mask the Taste and Reap the Nutritional Benefits

- Dairy Cow 101: Everything You Need to Know

- How to Keep Animals Cool in Hot Weather

HMG Trading | Beyaz Eşya İndirimli Fiyatları kıbrıs teknoloji market,kıbrıs teknoloji,teknoloji Kıbrıs,kıbrıs ta elektronik eşya fiyatları,kıbrıs teknoloji mağazaları,kıbrıs elektronik market,kıbrıs elektronik

HMG Trading | Beyaz Eşya İndirimli Fiyatları kıbrıs teknoloji market,kıbrıs teknoloji,teknoloji Kıbrıs,kıbrıs ta elektronik eşya fiyatları,kıbrıs teknoloji mağazaları,kıbrıs elektronik market,kıbrıs elektronik

I have been struggling with this issue for a while and your post has provided me with much-needed guidance and clarity Thank you so much

Ekrem Abi güvenilir siteler hakkında daha fazla bilgi edinin ve güvenilir online platformlara erişim sağlayın.

Ekrem Abi güvenilir siteler hakkında daha fazla bilgi edinin ve güvenilir online platformlara erişim sağlayın.

Ekrem Abi güvenilir siteler hakkında daha fazla bilgi edinin ve güvenilir online platformlara erişim sağlayın.

bokep indonesia terbaru

Child Porn – 12 years old Child Porn

This is such an important reminder and one that I needed to hear today Thank you for always providing timely and relevant content

Your posts are always so relatable and relevant to my life It’s like you know exactly what I need to hear at the right time

Your blog is a constant source of wisdom and positivity Thank you for being a ray of light in a sometimes dark world

I have recommended your blog to all of my friends and family Your words have the power to change lives and I want others to experience that as well

Your posts are so thought-provoking and often leave me pondering long after I have finished reading Keep challenging your readers to think outside the box

Your blog always leaves me feeling uplifted and inspired Thank you for consistently delivering high-quality content

Your blog posts never fail to entertain and educate me. I especially enjoyed the recent one about [insert topic]. Keep up the great work!

I love how this blog gives a voice to important social and political issues It’s important to use your platform for good, and you do that flawlessly

Your blog has helped me become a better version of myself Your words have inspired me to make positive changes in my life

You have a way of explaining complex topics in a straightforward and easy to understand manner Your posts are always a pleasure to read

Your writing style is so engaging and makes even the most mundane topics interesting to read Keep up the fantastic work

you’re acyually a justt right webmaster. The web site loading pace is amazing.

It sort of feels that you are doing any unique trick.

Furthermore, The contents are masterwork. you have performed a excellent job in this subject!

What’s up, the whole thing is going well here and ofcourse every one

is sharing information, that’s in fact excellent, keep up

writing.

This blog post has left us feeling grateful and inspired

197кm / 123 miles.

Your blog is a great source of positivity and inspiration in a world filled with negativity Thank you for making a difference

Thank you so much for putting this info together! My husband and I started a tiny herd a year ago and it is difficult to find this 101 cattle info. If you’re not from a ranching family and/or lack an experienced mentor it’s like recreating the wheel. I learned a lot from your podcast and in some cases it solidified my views and built confidence. I would love to see more info on cattle in the future — maybe on calving? Thank you!

Hi Melissa! Thank you for a wonderfully informative article on raising your own cattle. We are looking into raising a steer (or two) next year. When you overwinter your cattle, are they only given grass/orchard hay? I was talking to a local to me rancher and she overwinters hers with supplemental grain, which I did not want to do. Just trying to see if you have to grain them in the winter or I can keep the weight in them with hay. Thanks for your insight. And btw, I love the magazine. 🙂