If you’re thinking about using portable electric fence netting for cattle, poultry or other livestock, read this first! I’m sharing tips I wish I had known before I started, including how to best set up your fencing for the specific predators in your area.

I’ve been using electric poultry netting for my ducks and chickens for over three years now and was still so pleased to sit down with Joe Putnam from Premier 1. He taught me hacks for using electric fence netting, most specifically for keeping predators out!

Natural Remedies Made Simple

Start your home apothecary with confidence—even if you’re brand new. Learn how to choose the right herbs for your body using the simple principles of herbal energetics.

Discover how warming, cooling, drying, and moistening herbs affect your body—so you can stop guessing and start making remedies that actually work.

This past year we lost our entire flock of ducks during the winter to a coyote right outside our house! Now I’ve learned more tricks to keep the predators out, and keep my new flock of ducks healthy, happy, and safe.

The Hidden Cycle Keeping You Inflamed

If you’ve been feeling puffy, tired, achy, or wired-but-tired, this two-page guide will help you understand what may be happening behind the scenes — even if you’re eating “healthy.”

Download the Inflammation Flywheel Guide and learn:

- Where to start so you don’t feel overwhelmed

- The 5 most common drivers that keep inflammation switched on

- Why blood sugar swings, stress, and poor sleep feed each other

Join me for today’s Pioneering Today Podcast (episode #394) to learn more about using electric fence netting, including how much you need, how powerful of an energizer you’ll need, how to maintain the netting for longer life, tips for setting it up to avoid it shorting out, and so much more!

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

- Premier 1

- How Electric Fence Netting Works

- Best Fencing to Get

- Setting Up Electric Fence Netting for Specific Predators

- Using Electric Netting in the Snow

- How Long Will Electric Fence Netting Last?

- Lifespan of the Energizers

- Can You Recycle Batteries

- Modern Homesteading Conference

- More Posts You May Enjoy

Premier 1

Premier 1 is one of the leading companies when it comes to small-scale (and large-scale) homesteading. Their portable electric fence netting is perhaps how they became a household name, but that’s not all they offer!

On the Premier 1 website, you can order everything from fencing to meat processing equipment. With supplies like harvest baskets, home grinders and mills, home dairy supplies and all the poultry supplies from incubation to butchering you’ll need, there’s something for everyone.

You may not know that Premier 1 has a working farm where their products are continually being used and tested to improve what they’re selling.

Living in the Pacific Northwest, I was always skeptical of using solar-powered netting. It wasn’t until I went to a conference and learned more about Premier 1 netting that I figured I’d try it. Now, it’s the best thing I’ve ever used! Even in our overcast, drizzly climate, the solar power works great.

Joe also shared that Premier 1 offers sheep and goat advice where they have an on-staff nutritionist (and work with a licensed veterinarian) who can answer your questions. Though they can’t write prescriptions over the web, they can offer extensive advice regarding raising livestock. This is a huge asset to the new homesteader!

Be sure to check out Premier 1 to see all they have to offer! They also happen to be the sponsor for this podcast episode, so a huge thanks for that as well.

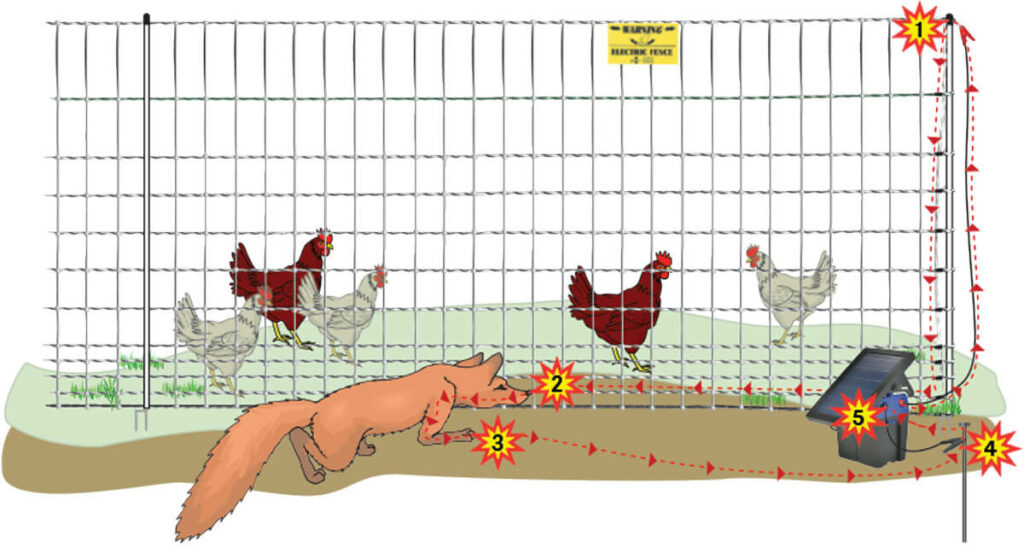

How Electric Fence Netting Works

Joe mentioned that many people are concerned with the power of the electric fence netting because if it’s strong enough to shock a cow, it must be too strong for a chicken (especially baby chicks).

He explains that the way the netting works is that the larger and heavier the animal, the more they come into contact with the ground. So a black bear, for example, is going to get quite a large shock compared to a chicken.

Since chickens are much smaller with smaller feet, they don’t make as much contact with the ground, giving them a lesser shock that’s appropriately strong for them.

They also have something called “Shock or Not” fencing to protect your baby chicks from getting even a small shock.

It’s pretty great the way the netting works for each different predator or animal.

Best Fencing to Get

The type of electric fence you’ll get will be determined by your needs. Because I’ve started mob grazing with multi-species, I asked Joe if there’s one specific electric fence he recommends that will work for all the animals.

He said the chicken netting is best because it’s four feet tall, which works for cattle, is tight enough for poultry and goats, and also works well for sheep. So if you’re looking for a “one stop shop” of a net, the 48″ poultry netting is your best bet.

It’s not, however, recommended for pigs because they root and turn up the soil. As the soil is turned up, it can bury the bottom line of the fence, which will short it out. This isn’t to say it can’t be used with pigs; it will just require frequent checks to ensure it’s working.

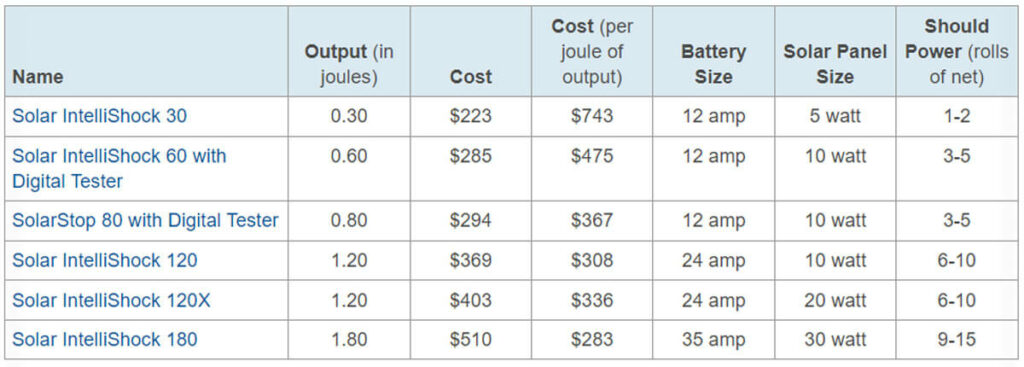

What Size Energizer is Needed?

Have you wondered how many nets you can string together before you begin to lose voltage? When setting up netting, you need to make sure you’re using an energizer that’s strong enough with enough output for the number of nets you’re using.

An energizer with more output can run more fences. Something I’ve learned over the years is that you’ll never regret getting more power for your energizer! We actually purchased one that was triple what we thought we needed at the Norris Farmstead, so I think we finally learned our lesson.

You want at least 3000 volts to your netting, so check often with your fence tester.

Unit Output

- .5-.8 Joule Units will run 3-4 strands of 100-foot poultry netting

- 1 Joule Units can run 5-6 strands of 100-foot poultry netting.

- 20 Joule Units (like they use at the Premier 1 farm) can run netting to a much larger area. This is ideal for larger operational needs.

Something to consider when setting up your netting is that when grass comes into contact with the fence, though it’s not much, each blade of grass will sap just a bit of energy.

This sapped energy can really add up, so it’s recommended to knock back the grass by mowing or trampling it down (or weed whacking) the perimeter of the area where the fence will be set up to eliminate the grass from touching the fence.

Setting Up Electric Fence Netting for Specific Predators

Electric fence netting will protect your livestock from coyotes, raccoons, bobcats, black bears, aerial predators and more. These are the tips I wish I had known years ago! You can actually set up your electric fence netting in unique ways to deter your specific predators.

- Aerial Predators: For those aerial predators like owls, eagles and hawks, it’s best to set up a narrow run for your animals. This makes it more difficult for the birds to dive down and grab a chicken. For further protection, you can crisscross some fishing line or reflective string across the top of the fence.

- Cougars, Mountain Lions & Bobcats: Since these predators can jump pretty high, it’s best to go with the taller netting. Then, angle the net outward. Once the animal gets a shock, it will usually look up to see if it can jump over the fence. Because it’s angled outward, it will appear to be above them and deter them from jumping over.

- Black Bear: Set up the fence normally. Because black bears have large bodies and large feet, they’ll receive quite a shock if they touch the fence. This is usually enough to deter them.

- Weasels: If weasels are an issue for you, you may need to look further than electric netting as a protective measure. Because they’re so small, they may be able to fit through the fence. If you still want to give it a try, start with the Shock or Not because it has smaller holes that may keep the weasels out.

Using Electric Netting in the Snow

When dealing with snow (unless it’s very dry snow or a small amount), it’s probably best to not use the netting as there are so many factors that can cause the netting to short out.

However, if you still want predator protection for your flock during the winter, you’re going to want to keep a good eye on the netting to make sure it’s not shorted out by snow.

We like to free-range our ducks in the winter, and though they usually stay in their tractor when it’s snowy, as soon as that snow melts, they want back out. Joe recommended simply testing the fence each day to make sure the snow hasn’t shorted it out; that way, they’re still protected from predators.

Joe also recommends setting up a pause barrier (in case the internal wire gets shorted out). A simple electric fence that’s about two or three strands should do the job. This will be what the coyotes (or other predators) hit before getting to the poultry netting, hopefully dissuading them if the snow has shorted out the netting.

How Long Will Electric Fence Netting Last?

Joe says they tend to get 7-10 years out of their netting at Premier 1. However, they’ve also had reviews of people using 20-year-old netting!

It depends on how you use them and how much damage they receive. If you’re continually pulling them through brush or setting them up in really hard soil, thickets, etc., this will reduce the overall lifespan.

Lifespan of the Energizers

The thing that goes out most on the solar energizer units is the batteries. Joe says this comes down to management. If you’re setting up your solar power unit in the shade or at an angle where it can’t get enough charge from the sun, it will still pull power from those batteries, draining them quickly.

It’s essential always to set up your panel to the south and follow the instructions for the best solar power. That way, you’re not just draining your battery within a month!

Joe recommends having a multi-meter or fence tester and frequently testing your battery to ensure it’s above the 12.6 voltage rating and not drawing below that too often. If they’re getting low, just top them off!

Can You Recycle Batteries

Joe recommends checking your scrap yard to see if they’ll recycle the batteries. This may vary from region to region. My scrap yard does!

Modern Homesteading Conference

If you’re planning on attending the Modern Homesteading Conference this year (2023), you can come meet Joe himself. If you’ll be in the Pacific Northwest region (specifically North Idaho), come see us on June 30-July 1, 2023, for the first annual Modern Homesteading Conference. Buy your tickets to the conference here!

More Posts You May Enjoy

- Raising Backyard Meat Chickens

- Troubleshooting Chicken Health & Best Herbs for Chickens

- Raising Chickens for Profit

- How to Can Chicken (SAFE & Easy Raw Pack Method)

- How to Butcher a Chicken at Home

- Integrating New Chicks to Existing Flocks

- Breeding Chickens Naturally: Selective Breeding for Eggs & Chicks

- Using Chickens in the Garden (13 Things You Need to Know!)

[fusebox_transcript]