Learning how to raise, butcher, and prepare homegrown pork for the best flavor is something every homesteader wants to know. Join me for this podcast with Brandon Sheard, the Farmstead Meatsmith as he shares his best tips for raising pigs.

I've discussed how to raise pigs here, including purchasing pigs, the space requirements, feed, etc. I've also interviewed Cathy Payne, discussing raising American Guinea Hogs here. I also did a follow-up podcast on whether raising American Guinea Hogs was worth it. But today's episode with Brandon is so fascinating, and I know you'll love it just as much as I.

Brandon Sheard, Farmstead Meatsmith

You may have heard of Brandon from the Farmstead Meatsmith. He came into traditional slaughter, butchery and curing after finishing his graduate work in Renaissance English Literature.

After marrying his wife Lauren, he quit his job at WholeFoods in the supplement department and started work on a small, multispecies and pasture-based farm in the Pacific Northwest.

After two years of working on the farm and managing the butcher shop, Brandon left and started Farmstead Meatsmith with his wife and kids.

They are self-taught in the art of traditional animal harvesting. Brandon and Lauren continue to provide the services of livestock processing, online education, and on-farm classes through Farmstead Meatsmith, with a little help from their eight children.

Farmstead Meatsmith prizes the pre-modern traditions of our fathers to enrich the family table and restore husbandry to prosperity.

Learn to Cook First

The best way to learn how to harvest, process, cut, and cure the animals you raise, is first to learn the final cause, which is to cook them well. The final cooked product is what will guide every process that comes before it.

This is how Brandon learned to cook as he was selling meat at a farmer's market and had to teach the people buying the product how to cook it.

For myself, this was how I was taught to cook our own grass-fed beef. Many people are used to grocery store beef and it has a very different flavor profile than grass-fed grass-finished beef. If it's not cooked correctly, it doesn't taste great. Here are some tips on eating nose to tail.

Learn These Three Methods

Brandon shares that the first step is to get rid of all the recipes you've used in the past and become skilled in braising, pan-frying and roasting.

This sounds so overly simplistic, but these three cooking methods will become your guide even to the butchery process.

The Most Important Ingredient

Brandon says the most decisive and important ingredients are the husbandry and the harvest – how the animal was raised and killed.

If those two things are done correctly, you're starting with the most delicious product you'll ever taste. Your job then is not to burn it to a crisp and be sure to salt it proficiently.

What to Feed Pigs

You may be wondering what's the best diet to feed pigs to ensure high-quality tasting meat.

Brandon shares that pigs are so flexible, and it's sometimes easier to talk about what not to feed them (more on that below). He's fed his pigs anything from a diet of day-old dumpster bread to an organic, high-quality hog mash.

You can also feed them leftover whey, which Brandon calls an ancient harmony. When feeding pigs whey, you can get away with a lesser quality grain because they're getting all the nutrients needed from whey.

Brandon also recommends, if possible, that pigs be allowed access to forest lands, especially if you have nut trees.

For our pigs, we've always harvested the fallen apples from the trees and mixed that into our pig's mash. We always thought the apples gave our pork a sweeter taste.

Brandon says it's likely due to the tannins in the skin of the apples, not necessarily the sugar content.

What Not To Feed Pigs

You don't want to feed pigs large amounts of fish emulsions. Depending on what you're using your pigs for will also determine what you should or shouldn't feed your pigs.

For example, if you're wanting to make prosciutto, it will be hanging and curing for up to two years to develop the correct flavor, so you should avoid soy if at all possible in the hog ration. Because soy is usually baked, the oil in the soil is already oxidized and can give the pig's fat a bitter flavor.

Harvesting Pigs

The Kill

The on-farm kill is the best way to kill an animal for butchering. The key to getting the most yield out of your pig, meaning not wasting any part of the animal, is to scald and scrape the pig. (Here are more tips for butchering large animals at home.)

Since Brandon left Washington State, he's pretty sure there aren't butchers who will come and scald and scrape your animals anymore. So knowing how to do this yourself is the best way to maximize your yield.

Also, the best way to kill a pig is with a bullet to the brain about 2-3 inches above the eyes.

Then you have to stick the pig just behind the jawline to allow all the blood to drain from the pig. You can harvest the blood to make blood sausage if you'd like.

Scalding

To scald the pig, the way Brandon did this for years was to find a tree branch about 16 feet off the ground where he can hoist the pig up.

He then used a 55-gallon drum on a very powerful jet propane burner. The jet propane burner allows the water to heat up to a scalding temperature (147° F) within about 20 minutes. Anything less powerful than that, and you'll be waiting for that water to heat up for an hour and a half.

You want to avoid over-scalding the pig, this is why the scalding temperature is so important.

Then lower the pig into the water (only half the pig at a time) for about 90 seconds. Lift the pig back out and wipe some of the hair to see if it brushes away easily.

If the hair doesn't scrape away easily, you can dip it back in for about 15 seconds, 30 seconds, or 50 seconds until that hair comes off. But don't over-scald because this will adhere the hair to the pig and make it more difficult to scrape off.

Scraping

Once you've scaled the pig, you begin scraping off all the hair, the outer layer of skin, etc.

Gutting

The next step is to gut the pig and harvest the heart, liver, kidneys, etc. Brandon recommends not using a sharp knife when doing this but rather using your fingers to avoid ripping through.

Hanging

Once the pig is scalded, scraped and gutted, you then hang the pig overnight in a cold area (butchering outdoors in the winter generally is sufficient, depending on where you live).

Curing Pork

Because not all areas have cold nights (or cold storage) to hang pigs after butchering, many cultures use salt to immediately cure the pork.

This will yield a different kind of meat, it's not necessarily the process you'll want to use for cuts like pork chops.

If you listen to the podcast, Brandon talks further about curing meat with salt. The steps are basic, and he talks about how it's impossible not to know when the meat has spoiled.

He also shares tips like keeping flies away from meat, using the correct amount of salt, curing for the right amount of time, etc.

He also shares that curing meat during the right time of year (generally winter) is most important because, most often, when meat is spoiled, it's due to flies.

I also have another podcast episode on dry curing meat here, this is the process of fermentation used for curing salami.

Modern Homesteading Conference

This is the first announcement for my upcoming Modern Homesteading Conference in 2023 (June 30-July1) in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho.

I'm excited to say that Brandon will be there doing a two-day demonstration from slaughter, butchering, to charcuterie.

We have limited tickets available, so if you want to grab your tickets at the lowest price they'll ever be offered, get them here.

If you want to learn the exact methods Brandon follows for curing meat, I highly recommend you become a Meatsmith member. Brandon also has some teaching videos on Abundance Plus (use code “MKNFREEMONTH” for a free month of streaming). If you haven't subscribed to Abundance Plus yet, I highly recommend it as it's a wealth of resources.

Where to Find Brandon

Be sure to follow along on Brandon's journey and learn more of the skills he teaches:

- The Farmstead Meatsmith website

- Watch Brandon on YouTube

- Listen to his Podcast A Meatsmith Harvest

- Take a class from Brandon

- Get on the list for pork shares

- Find Brandon on Facebook and Instagram

Melissa: Hey pioneers. Welcome to episode number 352. Today's episode is a very, very fun one. It is how to cure and store pork without a fridge or any type of cold storage, just an ambient room temperature. We'll also be talking about traditional pork butchering and animal husbandry, but you are going to love, or at least I think you're going to love once we get into using old school, traditional, homestyle butchery versus commercial type agriculture and butchery.

Today's guest, I am just thrilled to introduce you to, he is a wealth of knowledge on this subject, and that is Brandon Sheard. Now you may know Brandon's brand, Farmstead Meatsmith. You have probably seen stuff from him before, but he came into traditional slaughter, butchery and curing right after finishing his graduate work in Renaissance English literature. After marrying Lauren, he quit his job at Whole Foods in the supplement department and started work on a small multi-species and pasture based farm in the Pacific Northwest.

After two years of working on the farm and managing the butcher shop, Brandon left and started Farmstead Meatsmith with Lauren. They are self-taught in the art of traditional animal harvesting, and Brandon and Lauren continue to provide the services of livestock processing, online education and on farm classes through Farmstead Meatsmith with a little help from their eight children. Farmstead Meatsmith reprises the pre-modern traditions of our fathers to enrich the family table and restore husbandry to prosperity.

And when you get to the end of the episode, you are going to hear a very fun surprise and first time announcement of this on the podcast. So I can't wait for you to dive into this episode. Wow, I am so excited to have you on the Pioneering Today podcast. Brandon, welcome.

Brandon: Thank you for having me. It's great to be here.

Melissa: Yes. I have been following you for a while and thrilled to have you on and get to learn more from you. So I would love if you would just tell for those who maybe aren't familiar with your story or with what you're doing a little bit about how you came into the model of butchering that you now teach. And I feel like saying almost resurrecting the home butchering model.

Brandon: Yeah, well, I guess you could say it was by not being trained in the conventional way of doing that. The conventional way of butchering, which is all oriented towards the commodity form of meat, which really has little to nothing to do with the homestead kitchen. And so I really am self taught. I've been doing this for over a decade now, since 2010. The shortest way to put it is I had to learn. I learned how to cook meat and then I worked backwards from there to the live animal, which is why I always say, and to this day, it is my guide that the best way to learn how to harvest, process, cut to cure the animals that you raise is to first learn the final cause, which is to cook them well. And that, the finished cooked product is what will guide every process that comes before it.

So that was how I learned first how to cook because I was selling meat at a farmer's market, working for a small farm. And I had to teach all of our customers how to cook meat in order to help them buy into and understand the increased value of the meat that we were producing and selling and the increased price. They needed to take it home, cook it and have it be delicious and nourishing. And so I had to learn how to cook first, and that's where it all started.

Melissa: Okay. I really love that answer because I know a lot of what you teach and talk about is pork, but even with grass fed beef, because that's where I feel like a little bit more of my expertise lies in, and we have customers as well. They are excited to do grass fed because they've heard all the wonderful properties that are actually in the meat, as far as health value. That's how ruminant animals were meant to be raised, et cetera. But if they're only used to cooking what you would get from the grocery store, which is usually grain fed, and they start with the grass fed, a lot of times they do have a hard time cooking it and getting it to turn out right if they treat it exactly the same. And so, yes, like when you were talking, I'm like, "Yes," because there is a learning experience if you've not grown up with that or learning how to cook with that.

So I know you talk mainly, or at least I should say what I have heard you talk mainly on is with pork. So, because I feel like we just said that, and if we don't dive into this, I'm going to be getting some comments. So when it comes to pork, do you have any general tips? I know each cut probably has its own nuances on cooking, but you have any general tips on cooking pork well?

Brandon: Yes. And it's the same general tips that apply to the cooking of all the beasts that we eat commonly. And it's really to eschew all the recipes, to get rid of the recipes for pork or for any meat and to instead become skilled in three techniques, which is braising, pan frying and roasting. And it sounds just way overly simplistic. But to this day, that is still how I cook all meat and those three methods of cooking are my guides, even for the butchery process, because braising, pan frying and cooking is how you turn that meat into food. The braising is just a heavy pot with a lid and moisture. So you're cooking, usually tougher meat, low and slow with moist heat. Roasting is dry heat in an oven. And pan frying is just direct heat on a skillet.

And if you focus instead of on recipes, but on just getting good at those techniques, especially braising, I would say then there's not a single piece of any carcass that is not available to your kitchen. You can make it all delicious from the feet to the ears, to the tail, to the chops. You just have to get good of those techniques. And once you've mastered those, the most decisive and important ingredients in any recipe, and I think this goes for beef and pork, for all of them are the husbandry and the harvest, how the animal was raised and how it was killed. If those things are done well, then you are starting with the most delicious thing you've ever tasted. And your job is just don't burn it to a crisp and salt it sufficiently and it will be extravagantly delicious.

Melissa: Okay. I love that. And it's really, yeah, it's the fundamentals. Those are the fundamentals. Yeah. And unfortunately, in this day and age, a lot of us didn't learn some of those fundamentals growing up. So we're relearning them as, or I should say, not necessarily relearn, but some of us are learning those as adults or got away from that. Maybe our folks cooked that way, but we didn't for a period of time and are relearning them. So yeah.

With the pork, because porks are obviously not ruminants, they don't just eat, eat, eat grass. Just briefly, because I'm curious to see if it differs from what we have done in the past, but primarily giving them that good foundation. What are you looking at when you're feeding the pigs for optimal diet?

Brandon: Yeah, that's a great question. Cause pigs are, gosh, they're so flexible. They're so amicable. You can feed them so many things and they'll do very well on it, that it's easier to talk about what not to feed them. I've raised pigs on day old dumpster bread and wheat gleanings as I could get them. And I've raised them on really nice, organic, locally sourced hog mash with a full mineral spectrum. So in general, you just want to make sure that the pigs have their vitamins and their minerals. That's a big part of it. And that can either be supplied by a standard hog mash or that you get bagged, that's a complete nutrient, or by the leftover dairy from your milk cow or your dairy goat or a local dairy where you can pick up the whey that's left from cheese making.

And that's my ideal situation when I raise pigs is to have that source of dairy because that is just ... the piggery and the dairy are a ancient harmony that really works well because they get all of the minerals, all of the vitamins they need from the dairy, which means you can source more simple and more affordable grain rather than a more expensive hog mash. So again, there's so many ways to feed a pig well, but if I had to pick my way, I really love just basic field peas and barley and dairy of some kind, and I will soak the feed and give them that. And then of course, keeping them ideally in a forest. They're pretty good on pasture. Kunes will graze pasture, but they can be very hard on it and they can destroy it depending on your ground because of the rooting.

And so the forest is really, really where pigs want to be. Especially if you have acorns or nut trees in your forest, that's also wonderful for them. And then you can get much more detailed in the minutia of subtly flavoring the meat of the pig. And in general, again, that just gets to things to that you might want to avoid like excessive amounts of fish meal in the feed. Or even if you're trying to do long term curing, which means preserving the flesh of the pig indefinitely in ambient temperatures. So like a prosciutto that you cure, you wouldn't eat that until it's been hanging for two years.

Melissa: Oh my.

Brandon: And with in that case, if that's your focus, you might want to avoid soy if possible in the hog ration. Not because it's unhealthy for the pig. If it's organic soy it's good stuff, but it is usually baked, which means that the oil in the soy is already on its way to being ranted, which is not petrified. It's just oxidized. And it can give to the pig, the pigs fat in particular, a more bitter flavor, which is always a bummer because pig fat gets a bad rap. And it's usually because of soy rations, not because of pig fat itself.

Melissa: Okay. That's fascinating. We've actually never fed them soy. I should take that back. We have always fed on organic feed mix. So if there was soy in there, it was organic. I'm trying to remember if it was a no soy mix that I was able to get for them or not. But I find that fascinating, especially on the two years, which we're going to have to dive into that because when you're like at ambient temperatures ... that's one of the reasons we actually have never butchered our own pigs here is because we're just too ... temperature-wise we don't have a place to chill. I don't have a large enough unit to chill or to store it. And we don't have reliable cold days to ever schedule anything out. We're up and down.

I know you used to live in Washington, so you're a little bit familiar with that. We can have a cold snap and then two days later it can get really warm again. So for butchering, we've not been able to do that ourself other than just like, we're butchering it and then we're going to roast it that day or something. But we have always used ... because we have an abundance of apples here in Western Washington. So we have always towards the end, as soon as the apples start coming on, you get all the windfall and everything, all of our neighbors that everybody know, like if you've got apples you're not using we're coming for them. And so we'll actually make like a mash and mix that in with the feed and then feed them that. And we've always felt. Now, I don't know if it's true or not, but we've always felt that's imparted a sweeter flavor to the meat.

Brandon: Yeah, no, I think so. There's probably something to that. And it might not be necessarily because of the sugar, the juice in the apples, but more because of like pectins in the skin or antioxidant capacity in the skin and maybe even in the seeds or the stems like tannins, which actually they help pork flesh in the end be sweeter. So that's why pigs raised in a forest, it's just a good thing on many levels, not the least of which is just nibbling on twigs and particularly acorns, which have a ton of tanins. They're very tanic and bitter. That actually helps the pigs fat stay sweet because that's what it wants to do. It wants to stay sweet. And the moment you kill that pig and you cut it, just the exposing that fat to oxygen makes it start to go just a little bitter. And so you kind of, you mitigate that with those kind of feeds.

Melissa: Oh, this is fascinating, boy. We may have to have you on for some more episodes, but I'll try to keep us going here and not get too lost in the weeds because I love all of this type of information. I find it fascinating. So to the butchering though, because I know you really employ traditional, different than conventional. So when you are going to butcher an animal, walk us through specifically with pigs how you do that best set up. So for someone who's wanting to implement that at home, give us an idea of what that looks like using your methodology.

Brandon: Okay. And do you want to start from the kill or from after the kill?

Melissa: Well, I think we should probably start ... let's start at the beginning. Let's start the beginning, start with the kill.

Brandon: Start at the beginning. That's great.

Melissa: So for anybody who is ... I don't know if you're listening to this episode, I'm going to assume you would not be triggered by butchering. Most homesteaders choose to have livestock, and that is the most humane way in my opinion is for the animals to be processed on the farm and not taken anywhere else. As long as you're on board with that, please continue to listen with us.

Brandon: So true. That's a whole nother podcast right there too. We can talk about that forever. But yes, the on farm kill is by far the best way to dispatch your pig. And really, the best way to get the yield. The key actually, to getting the most yield out of your pig, meaning not wasting anything is to scald and scrape your pig. And that pretty much is something you'll have to do yourself. Since I left Washington state, I'm pretty sure nobody else will come to your farm and scald and scrape your pig for you. And that is really the key to the entire harvest, to eating everything but the squeal is that scald and scrape.

So the best way to kill any animal really is to understand its nature. And if you observe pigs for any amount of time, you can start to know what a pig is like and how a pig do in general. And then you can understand why the best way to kill a pig is with a bullet. Cause you'll notice that pigs are so cerebral, so intelligent. They have a very clear social order that they observe all the time. They never disobey their own rules. They're very strict about that. And so to the best way, the most humane way to dispatch them is with a bullet to the brain.

Whereas with another animal whose awareness is not as linked to their brain, but more to their feet and to the herd, like a sheep, a bullet might not be the best option. So it's really about discerning the nature of the animal and the harvest that it requires. So I shoot pigs in the brain with a 22 Magnum rifle, and there's a whole strategy to that. And in the end, it really boils down to being patient and to taking your time and to not yielding to that little anxious voice, that's telling you to squeeze the trigger before the shot is perfect.

And so it's really about waiting, waiting until you have the perfect opportunity, which sometimes that means you shoot a pig that's sleeping in the sun, because they're holding perfectly still. And sometimes you shoot them when they're drinking water, because that they're also holding still when they drink. So there's many ways to strategize that, but you take that shot and you're aiming for the forehead of the pig. So it's above that level of the eyes. It's not right between the eyes, it's about two and a half to three inches above the eyes. It's more in between the level of the ears and the level of the eyes and the pig will drop immediately. And then you need to bleed the pig out while its heart is still beating, because the bullet has taken out the brain, but the heart is still pumping. And so you stick the pig just behind the jaw line, which is going to release all of the blood from the carotid and jugular arteries, which is actually something that you can capture and create blood sausage with later.

So you just want to get a full flow, a stream of blood coming out of the pig and they'll convulsed for maybe two minutes. It's different with every pig and it's just death throes, and then they'll stop and then it's time to scald and scrape the pig. And there's many apparatus to help you do that. I mean, I did it for years, even as a business, out of the back of my pickup truck. I found the nearest tree branch that was about 16 feet off the ground and then I lashed a chain hoist to it. And then you set up a 55 gallon drum on a very powerful jet propane burner. And that enables you to heat water to the key scalding temperature in about 20 minutes, which is what you want because anything less than a jet propane burner and you're going to stand there for three hours waiting for the pot to boil as the proverb goes.

Melissa: Okay. I have a question for you. So when it comes to that 55 gallon drum, one, do you have any sources? Is there any ... I mean, I'm assuming if I had oil in it, we don't want to use it. I know that's pretty obvious, but is there any coating, non-coating? Is there anything we really need to be aware of when we're sourcing the 55 gallon drum to use?

Brandon: Yeah, that's a good question. I've always just found them on Craigslist over the years as I wear them out, and it's not practical to be too picky about the interior coating. They all have a coating on it, which helps it not rust. And eventually the coating does deteriorate, but you can get ... frequently you can find 55 gallon drums that had mango puree in them or something, something food safe. That being said, I have definitely, I've in a pinch grabbed drums that had like ship lacquer in them and you just, you can burn them out with fire and clean them with Dawn and really try to scrub them get them as clean as possible. But in the end, you're really only heating the water to 147 degrees Fahrenheit. So it's not a very ... it's not a rolling boil. It's not too hot.

Melissa: Okay. But that means I actually have some more options when I go to look for a barrel, because I think I was being overly picky and none met my specifications, so we didn't end up finding one.

Brandon: Yeah.

Melissa: Okay, thank you.

Brandon: They even make really nice stainless ones and I've never used those and they're really expensive, but they're out there. But yeah, and then that is the next step is to scald that pig. And the art of scalding a pig, and it is an art because it can go very badly, is to not scald the pig too much. It is not the case that the hotter the water and the longer the time the pig spends in the water, the easier the hair will come off. It is not how the equation works. It's actually possible to over scald the pig and that is what you want to avoid.

And so the key to that is to bringing the water up to 147 degrees Fahrenheit. And that's like, that's the million dollar tidbit of advice right there, 147 degrees. And then you lower the pig in. You only fit half in at a time. And then at about 90 seconds, you lift the pig out and you tug on the hair. And if the hair just, just pulls off effortlessly, like you can almost just brush your hand on the carcass and the hair just comes off, then you hoist the pig the rest of the way out and you scrape away. But if there's still a little resistance to it, you dip the pig back in again and check it again 30 seconds later, 50 seconds, at 90 seconds.

And you just keep checking it, because the point of that is to avoid keeping it in too long, because eventually you'll pass the point where the hair will come off. And in fact, the high temperature makes the hair adhere more stubbornly to the pig and it's adhering to skin that has been partially melted by the scald. So it's a really sisyphean disaster because you have to scrape harder to get the hair off, but you're scraping on a surface, the skin, which is partially cooked and melted and getting sticky.

So to avoid that you just check that hair frequently every 90 seconds or so, and keep the water at 145. I know I said 147, but 147 is what you want it at before the pig goes in. Then as you lower the pig in and you check the temp again, it'll drop a couple degrees down to about 145, and that is the scalding temperature. That's not burning, but it is hot enough to loosen the follicles and the epidermis. So the pigmented layer of skin is also going to peel off of the pig. So a black pig will become pink as you scrape. And then any bristles that are left over, you can shave with your scariest sharp knife. And then you have to eviscerate the pig once you've gotten all of the pigmented layer skin and the hair off, and that is ... any way you manage to get all the guts, all the tubes and the sacks out of there without puncturing them, that's how you do that.

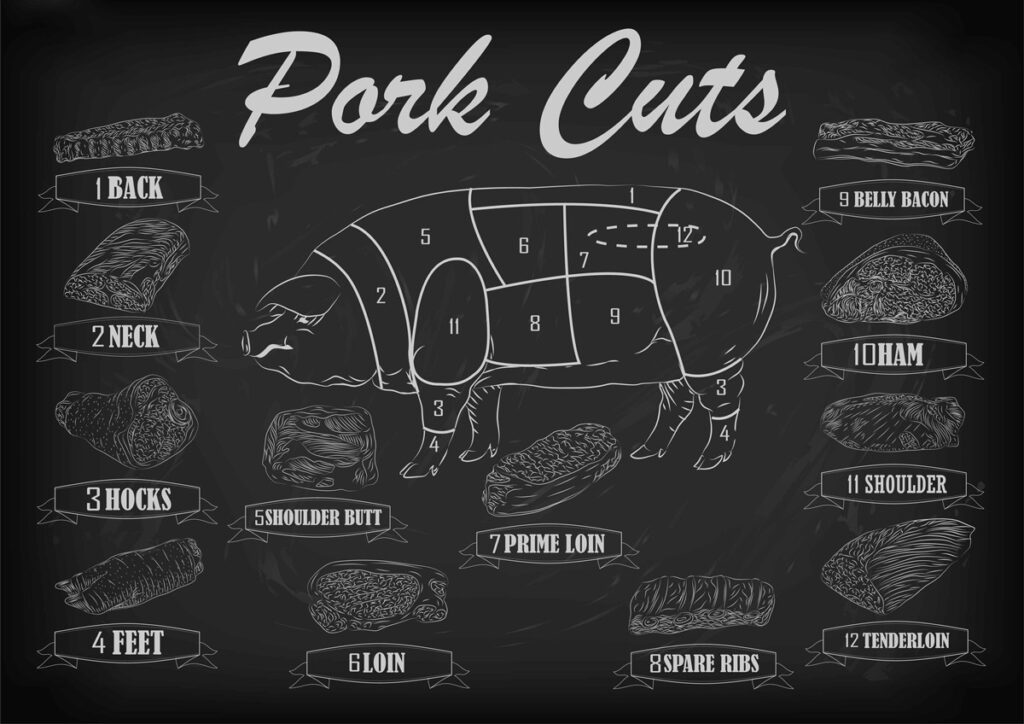

There's many techniques for it, but in general, just take your time and keep the knife out of the process. Use your dull fingers instead of your shark knife. Because frequently when we open up the intestines or poke the stomach it's with the sharp knife, that's usually the culprit. So you get to use to ripping fascia and pulling all GI tract and all the guts out. And then that's your second harvest. I guess you've already harvested the blood. Now you're harvesting the liver, the kidneys, the heart. And in fact, all of that is edible. It's all wonderful if you have the time to harvest it.

And so I usually tell people to pick their battles, and if you manage to eat the trotters and the head and the liver and the heart on your pig, in addition to all of its flesh and bone that is far away beyond any expectation on the conventional system, that's a great harvest. It's a great yield.

So then at that point, you split the pig down the middle once you've got all the guts out and then it goes to chill. And honestly, if you do this in December ... and I would say, Melissa, even in the Pacific Northwest, if the temps, they're not even freezing at night, maybe you're just getting down into the low forties, it only needs one night. You could just hoist that pig a little higher up in the tree you're hanging it from and go inside.

And if you're just doing one night, it's not that much time for it to get molested by critters and certainly pick the winter, obviously. Not just for the temperatures, but it's relatively fly free. So, the Pacific Northwest, this is the time of year to do this is after the first little cold snap that we get, frequently in January. It's a great time to do it after that point. I mean, I've even done it as early as the end of November, just depending on the year. And then the very next day you will have a chilled, rigid carcass and ready to portion, to cut and then to put some of it on the salt and some of it in the freezer, depending on how you want to do that.

Melissa: Okay. So I have a question. When you're splitting it in two, are you using a super big sharp knife, like some type of saw, what are you using to split the carcass into?

Brandon: Yeah. So you would use a bone saw. That's what I recommend for people. You can do it with a Cleaver. It takes a little more skill, some good aim, but in the end, just go ahead and get a bone saw. You could make a saws all sort of work if you can get one without paint on the blade, you don't want that nasty paint on your pig. And it's not a fixed blade, so it can wander. It can be tricky to stay nice and straight on the spine when you're using a Sawzall. So I just say, get a bone saw, because you'll use that for the butchery day as well. And for the rest of your life on your farm, just get a bone saw. They have replaceable blades, so you'll have it forever

Melissa: Love that. Now I'm curious because I have always been under the impression that you do not hang and age pork like you do with beef. Like we will cold dry age our beef, we prefer 21 days, but depending on how much fat layer it has, et cetera. And so I've always thought that just like you're saying that pigs, you're going to chill them overnight and then move right into it. We're not dry aging them. But I did hear, and it could be completely erroneous which is why I'm asking you. Somebody said that you can actually dry age pig. Have you ever heard of that? Is there truth to that?

Brandon: Yeah, there is. And I think traditionally the way that we have achieved the effects of dry aging on pig, similar to beef is by curing it with salt. That's just what we've always done. So it's a new thing. It's the fun new thing that we can do by virtue of our ability to control climates and temperature through refrigeration. So it's a new thing that'll be on fancy restaurants, and yes, even if you have a standard walk in and you pop a dehumidifier in there, I don't care what meat you put in there. It could be pork, definitely beef, whale I'm sure would do it. And you flip on that dehumidifier in that cold environment, all the meats just going to dry out. It's never going to spoil. Eventually it will just all be jerky. It'll just be totally dry and adhering to the bone. So if you can keep the environment dry, absolutely you can dry age pork.

Melissa: Oh, interesting. Okay. Well I did officially learn something new on that, because I wasn't sure if that was true fact or not. So I know you employ salt. And you even use salt with the pork, and it doesn't have to then be in stored in a cold ... well, I should say like a freezer or even a fridge environment, is that true? Or on certain cuts? Certain types?

Brandon: Yeah. So we could go from one end of the spectrum and say at no stage do you need a cool environment ever, and then we can work back from there. But because it is possible. You're in the Mediterranean and you kill your family pig, the backyard pig. And it just doesn't get that cold there. There's really not that ideal time when it's refrigerator outside, like you have in Washington. And so instead of chilling everything right after the evisceration, when the meat is still warm with body temperature, it goes into the salt drawer, which is what peasants used to keep in their yard, in a covered place. And it's basically exactly what you'd expect, a really large drawer and all the meat just goes in there and you that's how you get your prosciutto and your [inaudible 00:28:28] and your pancetta.

And so it is absolutely possible to do this with just salt and not even the winter. It just, you change the way you prepare the pork, you end up with more salty pork and you eat it differently. It's really not the preparation that would give you pork chops, for example. It's all cured meat. So you could do that. I think that the easiest thing, especially in the Northern hemisphere where we smoke all of our curing meat, because we're heating our houses with wood in general historically, is to just do it in the winter when you have that one night of chill and then you can do all the cutting the next day. And then you're still in the winter, so you can definitely cure things just in bus tubs. And really, the temperature is not that big a deal.

The biggest threat would be flies to the keeping of that meat while it's on the salt. If flies can get in there, they can spoil it. And then if you wanted to take it one more step into civilization, you could get a spare fridge. And the main advantage of the spare fridge is that it's a fly free zone. So you kill your pigs. And then you're doing the cutting the next day and you're putting things on salt and bus tubs. And then you just put that salted meat in your curing refrigerator, in your garage. And one bus tub takes up one shelf and you can cure many pieces of meat and one bus tub for sure. And that's usually the most common way to do it. And that's the great way to go.

Melissa: Okay. I find this so fascinating because I feel like ... I used to in high school, I had to go get my health permit thing because I worked in local restaurants, et cetera, and throughout high school. And so you're like, oh, meat never sits out at room temperature for more than X amount of minutes, which I've already forgotten. So I just, I find this fascinating because I feel like a lot of our modern society and food rules, I'm doing air quotes, which I know you guys can't see that though. Like when you hear that you don't ever put meat in a fridge or freezer. I know a lot of people are like, "Oh my gosh."

Brandon: Oh my gosh. Yeah. And it's understandable because a lot of the meat that they are writing those codes for is already filthy and subjected to aerobic environments. And it's already very fragile and on the verge of spoilage. In fact, anyone who works in a restaurant kitchen, or even in a butcher shop knows that the meat is covered in a slime. And that slime is bacteria. That is spoilage bacteria. And that is ubiquitous. That is every piece of meat. And that's because when it comes from the slaughterhouse, they want it to be shipped all across the country in plastic. So you're harboring moisture, you're trapping moisture in plastic and you're creating just an instant colony of spoilage bacteria.

And so yes, that very fragile meat that's already basically on its way out, you do have to be really careful about it, because it's just, it's already almost there. Whereas in your backyard, I mean, people are frequently surprised about this and when they first kill their animals in their yard, they're always surprised. Wow. It just wasn't that bloody, it wasn't messy. It wasn't sticky. It wasn't gross. And the meat didn't smell and it's like, yeah, that's because it's clean and the food miles are measured in the steps from your back door to where the pig is, and that gives you a ... it's a whole different animal. It's not just a different in degree, but in kind from the meat you're working with at a restaurant or retail butcher shop.

Melissa: Yeah. I completely agree because growing up, I was very fortunate that our beef, not other animals, but beef when I was growing up, we always raised our own beefs was always that. And then even when my husband and I got married and moved out of my dad's house and we got married, same thing. We bought beef from my dad until we started raising our own. And anytime I had ever had to cook store bought beef, I can't even eat it afterwards.

The difference that you're explaining, until someone has gotten to experience that for themselves, you don't even realize how bad it is until you move to the other. And yeah, you're right. There's extra liquid and it's not rotten when we're buying it. I know what a complete rotten meat smells like, unfortunately. But it has this weird odor, almost makes my stomach just like clench and feel nauseous. I can't cook with it.

Brandon: Yes. And I think that is one of the most discouraging things to people learning how to cook well and then want to raise good meat because it's hard to convince them of how effortlessly delicious it is. Cooking is easy when the meat comes from your backyard. It's effortlessly delicious.

Melissa: Yeah. Oh yeah. I agree so much. So back to the salting things though. I do have a couple of questions. So when we've got it in the bus tubs with the salt, then when you go to prepare it ... now I've had prosciutto and things where you're slicing that and you're eating it, you're pairing it with cheeses and different things like that to combat or be a good flavor profile with the saltiness of the meat. But if you're used to having your frozen sausage, say your ground sausage or even your pork chop, a ham is already salty, but are you pulling these out and you're rinsing them off before cooking or you just know that they're going to be very salty or can you walk me through that a little bit?

Brandon: Yes. Yes. And the tricky thing about walking anyone through that is all the possibilities that you just mentioned absolutely work. So there are more ways to do this, it's so flexible and easy, then there are not to do it, which is weird, but it really depends on what you're going for.

This is where you learn more of the subtleties of curing. Usually the differentiation between each cut is what gives you the flavor. So the different physiology, so like belly. Pork belly is what we usually turn it into bacon. Now you can also cure some of the shoulder and you can call it coppa. But when you cure the shoulder and the belly, it's the same curing recipe. It's identical. The difference is in the physiology of that muscle. And so, and then what you do with it after you take it off of salt.

So in the example of bacon of belly bacon, and this is assuming you want your bacon for breakfast meat, you want to be able to slice it and fry it for it not to be too salty and delicious. That's only going to be on the salt for four or five days. And then you take it out of that tub, you rinse it, you dry it and you hang it ... and you can in your kitchen, again, not in any temperature controlled environment, you just hang it in your kitchen, starting in the winter. When the flies are less populous and aggressive, and then you slice it and fry it right away. And it's delicious and it's wonderful. And you do the same thing with the coppa, with that shoulder muscle. But instead of slicing it and frying it right away, you just let it hang for eight months.

You'll leave it there and then it'll get cobwebs on it. It'll get dusty and it'll just dry out. It will slowly dry. And then the way you eat that is you slice it very thin and you just eat it raw. And that's what a prosciutto is except for not eight months, it's like two years. But in the end, it's all the same recipe that gets it to that point. And you just develop your own idea of what best serves your kitchen. Like we want more bacon, we want more coppa, we want more guanciale or prosciutto. And that's really where the only subtlety comes in curing.

Melissa: Okay, I am so intrigued and you're going to laugh at me, but if something ever were to go wrong in the process, I'm assuming that it would just start to smell like rancid meat. And you would know that a fly, something had gotten in there. And does that happen?

Brandon: Yes. That is such a great point, because we're dealing with whole muscle cures. So not salami. Salami is actually preserved through fermentation. So that's a different process. The cures I'm describing bacon, prosciutto, pancetta, coppa, those are whole muscles. So the process that curing them is very simple. We're just drying them out. That is all it is. The water is being removed and bound by the salt and they're drying out. So the things that go wrong with those cures are aromatically unmistakable. It goes real wrong. And you know it, which is great because what that means is you're never going to accidentally eat or feed someone else putrefied meat that's hanging in your kitchen. It's not going to happen.

You're not even going to be able to live in the same house as the bacon that's hanging there. It's going to smell like everyone knows it smells. It's a dumpster behind a restaurant at the end of July like that anaerobic, rotting, horrible petrifying smell. So spoilage is obvious in the case of whole muscle cures. And that should actually be an encouragement to just go ahead and do it, knowing that if it goes bad, it goes unmistakably bad if that make sense.

Melissa: It does. Actually, that reminds me a lot of with vegetable ferments, because really that's been my experience in vegetable ferments. When it's totally inedible it, you know it.

Brandon: You know it.

Melissa: It's not like canning where botulism is undetectable to smell, taste, sight, et cetera. Okay. And when it does go bad, is it because you either didn't have enough salt ratio or leave it in the salt long enough or there was fly contamination? Or I guess I'm curious as to what would cause it to go bad to just help to try to mitigate that as much as possible?

Brandon: Yeah. So by far and away, the most common cause of it is slaughtering your pigs and curing them out of season. So doing it in the summer. That is usually what does it, and it's usually flies. Flies get to it and they lay their eggs on it. And they will usually be attracted to where there is still blood in the meat, which is really only something you worry about in a prosciutto. The belly of a pig, the capillaries are so tiny there's not huge reservoirs of blood in there just waiting to be populated by a bacteria. So bellies, it's not even really a thing.

But it's more with the back leg, your big ham or prosciutto that you would hang for two years, the femoral artery can still have some blood in it. And if there's enough flies around, they'll be into that and they can get there. And if it's hot enough, if it's like 75 degrees in your house and you rinse a prosciutto off, you rinse the salt off prosciutto, dry and hang it, it might work, but it might be just too warm. And that warmth will encourage the putrefaction of that blood next to the femur. And you can lose prosciuttos that way. So it's usually just doing it out of season. It's usually flies. And again, it's obvious, you always know.

Melissa: Okay. Oh my gosh, there is so much, but I want to keep this episode consumable. And so I am excited because this is the first announcement on the podcast that we are having the modern homesteading conference in 2023 in Idaho. We'll have a link in the show notes, the blog post that accompanies this episode. But Brandon is going to be there doing a two day live demonstration. It's open to all ticket holders, included with the cost. And he is going to walk us through from the slaughter, the butcher, the cutting, and then into charcuterie on the second day.

So, if you are listening to this and you're like, "Man, I really want to see this. I really want to learn this," then that is coming your way. And I am so excited. I can't wait. I can't wait to be there. And to I'm the charcuterie part just has me fascinated and I can't wait to dive in and learn more.

Brandon, thank you so much for coming on this episode. We're thrilled to have you at the conference. And for those who are like, "Man, I don't know if I can wait a year," they want to follow along and learn more about the type of stuff you do, where is the best place for listeners to connect?

Brandon: While they can go to my website, FarmsteadMeatsmith.com. We have an online membership that we host there with an archive of over 50 videos on doing all of this stuff on multiple lives, all oriented towards the domestic scale, the small scale. And we've got a YouTube channel and a podcast called MeatSmith Harvest. That's that's everywhere that podcasts are. And yeah, and then we'll just see you at the conference.

Melissa: Awesome. Well, I'm so excited. Thank you so much for coming on.

Brandon: My pleasure. Thank you.

Melissa: Well, I hope that you enjoyed that as much as I did. Brandon is just a wealth of information, and I hope that you attend the modern homesteading conference. A little bit more details about the conference. It will be June 30th and July 1st of 2023, and it will be held at the Kuney fairgrounds in Coeur d'Alene Idaho. We do have a limited number of people that can be on site as you would well imagine with a live event. So if you plan on attending, highly recommend jumping over to modernhomesteading.com, modernhomesteading.com and getting your tickets. There are general admission tickets, and there is also VIP tickets, and they are both on early bird, which means you can get them at the lowest price that they will ever be for this event. And you can also see who some of our other speakers are.

Joel Salatin is one of them. Carolyn and Josh Thomas from Homesteading Family. Of course, Brandon, myself and there are a plethora of other speakers. We will be adding more speakers to that roster. So pop on over, grab your ticket if you think you're going to be coming, or you want to come before they sell out or before the price goes up. Because as I said, there is a limited number of tickets that we can offer at the early bird price. But you guys, I am so excited for this.

So many of you, anytime I have mentioned going back east to teach at some of the homesteading conferences on the east coast have said, oh, please, if anything is ever available on the west, please let me know. Well, there wasn't anything that I could find. So myself and my partner, Katie Millhorn from Millhorn Farmstead in Idaho, decided that we would create our own. So I can't wait to see you there. Thank you so much for hanging out with me. Until next week, blessings and mason jars for now, my friends.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.